Editor's Note:

To delve deeper into issues related to the handling of assets involved in cases under the implementation of the "Private Economy Promotion Law," and to foster a positive interaction between the healthy development of the private economy and judicial practice, the "Special Symposium on the Implementation of the Private Economy Promotion Law and the Handling of Case-Related Assets" was grandly held at the Central University of Finance and Economics on June 15, 2025. The event was jointly organized by the School of Law at CUFE and the Research Center for Litigation Systems and Judicial Reform at Renmin University of China, with co-sponsorship from Beijing Xinglai Law Firm.

Professors Chen Weidong, Cheng Lei, Liu Jihua, Li Fenfei, and others from the Renmin University of China Law School; Professors Guo Hua, Li Wei, and others from the Central University of Finance and Economics Law School; along with legal scholars and experts from institutions such as China University of Political Science and Law—joined forces with practitioners and experts from top-tier judicial bodies like the Supreme People's Court—to engage in an in-depth discussion centered on key topics including corporate operational autonomy, corporate property rights, corporate digital assets, and the handling of assets involved in legal cases.

At the meeting, Attorney Cheng Xiaolu, Chair of the Partner Conference at Beijing Xinglai Law Firm, delivered a speech as a representative from the practical legal department during the session titled "Corporate Operational Autonomy and Disposal of Assets Involved in Cases," focusing on the topic "Curbing Extraterritorial Enforcement Driven by Profit Through Standardized Jurisdiction."

Cheng Xiaolu, Chair of the Partner Meeting at Beijing Xinglai Law Firm

Dear Professor Chen, esteemed experts, and colleagues:

Good morning! It’s my great honor to speak here today as the sole representative from a practical department and as a lawyer. My topic is "Curbing Extraterritorial Enforcement Driven by Local Interests Through Standardized Jurisdiction." Earlier, Professor Chen (Weidong) emphasized the importance of clearly defining jurisdictional rules during his keynote speech. Meanwhile, several experts who joined the discussion also highlighted two key aspects of regulating enforcement activities involving businesses: first, jurisdiction; and second, the handling of assets tied to the case. Indeed, jurisdiction serves as the very starting point of criminal proceedings. By standardizing and clarifying jurisdictional rules, we believe it can fundamentally curb extraterritorial enforcement practices motivated solely by local interests—something that, from our legal perspective, holds critical significance.

I. Legal Breakthrough in Standardizing Off-site Enforcement Policies

The "Private Economy Promotion Law" marks a milestone in institutional reform by elevating the policy call for regulating out-of-area enforcement into a formal legal requirement for the first time. Previously, many policy proposals merely urged against using administrative measures to interfere in economic disputes, but there had never been explicit legislation clearly restricting out-of-area law enforcement practices. Since the end of last year, the phenomenon known as "oceanic fishing"—where authorities from one region aggressively pursue cases or impose jurisdiction in another—has intensified, drawing increasing attention from both practical and legislative bodies. On December 4 last year, the National Development and Reform Commission issued the "Guidelines on Building a Unified National Market (Trial)," which explicitly states: "No illegal out-of-area enforcement activities or extraterritorial jurisdiction shall be conducted; instead, profit-driven enforcement and judicial actions must be prevented and corrected in accordance with the law."

II. Reasons Behind the Frequent Occurrence of Profit-Motivated Enforcement in Different Locations

Why does profit-driven, jurisdiction-hopping enforcement frequently occur? There are two main reasons:

(1) Profit Considerations from Confiscation and Fines

Penalty and confiscation revenues are driving profit-driven enforcement practices in other jurisdictions, as governments at all levels rely on these funds as a key revenue source. In some cases, officers' earnings are even tied directly to the amount of fines and confiscated assets collected—though this specific issue isn’t the main focus of my remarks today.

(II) The Current State of Law Enforcement in Addressing Alienation

1. Generalization of Jurisdiction by Region

The Criminal Procedure Law establishes jurisdiction principles based on the location of the crime and the suspect’s residence, generally prioritizing the location of the crime. However, if the suspect’s residence is deemed more appropriate, jurisdiction shifts accordingly. The "Regulations on Handling Criminal Cases by Public Security Organs," along with the "Regulations on Handling Economic Crime Cases" jointly issued by the Supreme People’s Procuratorate and the Ministry of Public Security, provide further interpretations of what constitutes the "location of the crime," adopting a rather broad definition. Specifically, locations where the criminal act occurred, was carried out, prepared, initiated, concluded, or even merely passed through—including areas where the crime unfolded continuously or repeatedly—as well as places where the victim’s interests were directly violated, are all considered part of the crime scene.

This leads to a situation where, in practice, the jurisdiction for reporting disputes depends entirely on where the whistleblower chooses to file the complaint. When handling mutual accusations between shareholders stemming from economic disputes, the location of the shareholders may be redefined as the "place where the crime was committed," while some regions even classify shareholders directly as victims. A notable example is the 2019 China Law Review Cup Top 10 Cases of Acquittal—specifically, the case involving Wang Moujun and the misappropriation of funds. By successfully challenging jurisdictional issues, the case was shifted from Hubei, the shareholders' home province, to Shandong, the location of the victimized company. More recently, in April of this year, the Ministry of Public Security issued the "Regulations on Jurisdiction over Inter-Provincial Enterprise-Related Criminal Cases," which narrowed down the existing legal provisions on territorial jurisdiction and established the principle of primary jurisdiction based on the location of the main crime. The practical implementation of these regulations has already yielded significant positive results.

For instance, in the first half of this year, we assisted a shareholder from a chemical company in filing a criminal complaint against another shareholder for allegedly exploiting related-party transactions to harm the company’s interests. Originally, we had planned to file the report at the shareholder’s hometown—where the accused individual was registered—but due to newly issued regulations from the Ministry of Public Security regarding jurisdiction over cross-provincial economic crimes involving enterprises, we ultimately decided to lodge the complaint in another province, at the location of the victimized company. There, we submitted a detailed legal opinion along with supporting evidence. Following a thorough review of both the documents and our legal analysis, the local public security authorities officially initiated a criminal investigation into the case.

2. Abuse of Designated Jurisdiction

In cases involving organized crime and evil forces, the abuse of designated jurisdiction is a serious issue. Often, the so-called "black bosses" are local entrepreneurs who hold substantial assets. Typically, provincial public security departments, citing Article 22 of the "Regulations on Handling Criminal Cases by Public Security Organs," designate these cases to be investigated by other cities within the province—something that, in itself, poses no problem. However, the real concern arises when city-level public security authorities, without seeking approval from the provincial department, unilaterally assign the case to district or county-level agencies for investigation, effectively determining the subsequent stages: whether to recommend arrest, initiate prosecution, or decide the level of trial.

For instance, in Liaoning’s “11·13” organized-crime case, the Liaoning Provincial Public Security Department had originally designated the Fuxin Municipal Public Security Bureau as the competent authority. However, the Fuxin Municipal Bureau was unexpectedly reassigned—without proper authorization—to the jurisdiction of the lower-level A District Bureau (which only handled procedural tasks, while the actual investigation remained under the jurisdiction of the municipal bureau). Yet, the T District Bureau, disregarding the principle of transferring cases within the same level and district, arbitrarily forwarded the case to the B County Prosecutor’s Office in Fuxin City for arrest requests and prosecution review. Notably, this entire process occurred without prior approval or designation from the higher-level provincial prosecutor’s office. It wasn’t until lawyers reviewed the case files and raised objections that the provincial prosecutor’s office retroactively approved the transfer, officially designating the B County Prosecutor’s Office as the competent authority. By then, however, the unauthorized arrest measures had already been carried out.

3. Jurisdiction at the same level is virtually non-existent.

Article 23, Paragraph 3 of the "Regulations on Procedures for Public Security Organs in Handling Criminal Cases," as well as the "Provisions on Several Issues Concerning the Handling of Crimes Involving Mafia-like Organizations" issued jointly by the Supreme People's Court, the Supreme People's Procuratorate, and two other ministries, both outline the authorities responsible for reviewing and approving arrests and initiating prosecutions in mafia-related cases under designated jurisdiction. However, in practice, cross-district transfers at the same level are often handled quite arbitrarily.

In a major organized crime case we're handling in a city in the southwestern region, the city Public Security Bureau's directly affiliated division has blatantly disregarded the principle of jurisdictional competence at the same level. Instead of following proper procedures, it has simultaneously forwarded the case—depending on the specific needs of the investigation—for review and prosecution to both the municipal-level Municipal Procuratorate within its jurisdiction and the district/county-level Procuratorates below it, all without going through the necessary formalities. As a result, the very concept of "jurisdictional competence at the same level" has effectively become meaningless.

For instance, in the Liaoning 11·13 organized-crime case we handled, after the public security agency from District A of the city was assigned jurisdiction, the case was transferred to the B County Procuratorate for review and prosecution. However, when the lawyer discovered that their client might have been subjected to coercive interrogation and torture—situations warranting a formal complaint, appeal, or request for oversight—the lawyer couldn’t file an oversight application directly with the current reviewing and prosecuting B County Procuratorate. Instead, they were forced to apply through the corresponding District A Procuratorate, which, ironically, is neither responsible for reviewing arrest warrants nor handling prosecution itself. As a result, effective oversight became virtually impossible. Moreover, it’s worth noting that the actual investigative authority rests with the municipal-level public security agency—this arrangement was deliberately designed solely to ensure that the case’s second-instance review would remain confined within the designated city, effectively bypassing any broader accountability mechanisms.

So, you see, the criminal procedure jurisdiction system, originally designed with a court-centric approach, has in practice evolved into an investigation-centric model.

4. Lack of Relief Mechanisms

The investigating authorities accepted and approved the arrest despite lacking jurisdiction. Although they later retroactively completed the procedures for designating jurisdiction, it remains questionable whether the legality of the earlier proceedings can still be validated. For instance, in an economic crime case involving Taiwanese individuals that we handled in Qingdao, following longstanding judicial practice, cases involving Taiwanese nationals—similar to those involving foreign nationals—were traditionally centralized under the jurisdiction of the L District Prosecutor’s Office in Qingdao. However, no explicit legal provision mandated this arrangement. Two years later, the court became aware of the jurisdictional issue and returned the case file to the L District Prosecutor’s Office, citing lack of proper authority. In response, the L District Prosecutor’s Office swiftly obtained the necessary procedures for designating jurisdiction and promptly resubmitted the case to the L District Court. The court, in turn, also retroactively formalized the designation of jurisdiction, resulting in the creation of a new case number within the court’s case management system. The L District Court has reopened the trial with a new case, However, the original old case was already nearing the end of its statutory review period—any extension would require approval from the Supreme People's Court. But once it’s assigned a new case number, the court can openly and legally recalculate the review deadline from scratch. Thus, obtaining a trial period that is actually longer than that for cases under normal legal jurisdiction, This means that, by operating in this manner, the judicial authorities have inadvertently benefited from exercising jurisdiction illegally. Fortunately, in this particular case, we promptly voiced our concerns, and after the authorities took notice, the case was swiftly resolved—most notably, the critical charge of embezzlement of office duties was dropped. However, should similar situations arise in other cases, it could potentially lead to prolonged pretrial detention.

Additionally, according to current regulations, while the defendant and their defense counsel can raise objections regarding jurisdiction, they are limited to submitting these concerns directly to the investigating authority. However, this very authority is itself designated by a higher court, and its legitimacy in hearing the case stems from the authorization granted by that superior body. Therefore, if there’s an issue with the jurisdictional designation, the problem ultimately lies with the higher court—not with the agency that was originally appointed. As a result, bringing jurisdictional concerns directly to the designated lower court or prosecutor’s office is unlikely to resolve the issue. On the other hand, if such concerns are instead reported to the higher court that made the original designation, the only available channels become formal complaints or petitioning processes. Unfortunately, these higher-level complaints and petitions typically get passed down—step by step—to the very lower courts or prosecutors’ offices that were initially assigned the case. In essence, this means there’s virtually no effective remedy available, making it nearly impossible to achieve any meaningful resolution.

III. Recommendations for Standardizing Jurisdiction

(1) Limiting Jurisdiction by Territory

Clearly define the jurisdiction based on the crime's location, especially in cases involving multiple districts or provinces. In accordance with the new regulations issued by the Ministry of Public Security in 2024, establish the principle of "jurisdiction over the primary crime location." If the primary crime location is unclear or disputed, the jurisdiction will be determined by the location of the victimized entity.

(II) Designated authorities are strictly prohibited from arbitrarily re-designating lower-level jurisdictions.

It is strictly prohibited to subcontract cases to the next lower jurisdiction without approval from the designated superior authority, ensuring that the case’s hierarchical level aligns with its significance. This measure prevents arbitrary reductions in the level of review, which could otherwise infringe upon the defendant’s legal right to be tried by a higher-level judicial body. For instance, Article 8 of the "Implementation Measures for Designated Jurisdiction over Cases Involving Crimes Allegedly Linked to Mafia-like Organizations," jointly issued by the three agencies—Public Security, Procuratorate, and Court—in Shandong Province (Document No. Lu Gong Chuan Fa [2011] 2030), stipulates: "Cases under designated jurisdiction by the Provincial Public Security Department, Provincial Procuratorate, and Provincial Court shall be handled by the designated municipal-level public security organs, people's procuratorates, and people's courts." Based on the case details, after obtaining approval from the superior authority , the subordinate unit may be designated under the jurisdiction as stipulated in Article 5 of these Measures, and the copy of the "Decision on Designated Jurisdiction" must be submitted to the higher-level unit for record within ten days after the decision is made.

(III) Clarify that jurisdictional transfers at the same level are limited to transfers within the same district.

Cross-regional and cross-level transfers must be approved in advance by the superior authority, preventing designated agencies from arbitrarily moving cases across regions or levels while disregarding legal regulations.

(IV) Establishing a Jurisdictional Objection Procedure

Grant lawyers a statutory channel to lodge objections with the higher authority that made the jurisdictional designation (other than the designated agency itself), and, if necessary, organize hearings. The higher authority must provide a written response within the statutory timeframe, and applicants should be allowed one opportunity for reconsideration—thus addressing the current situation, where challenges can only be pursued via complaints or petitioning processes with no guarantee of acceptance.

Lawyer Profile

.

Cheng Xiaolu

Beijing Xinglai Law Firm

Chairperson of the Partners' Meeting

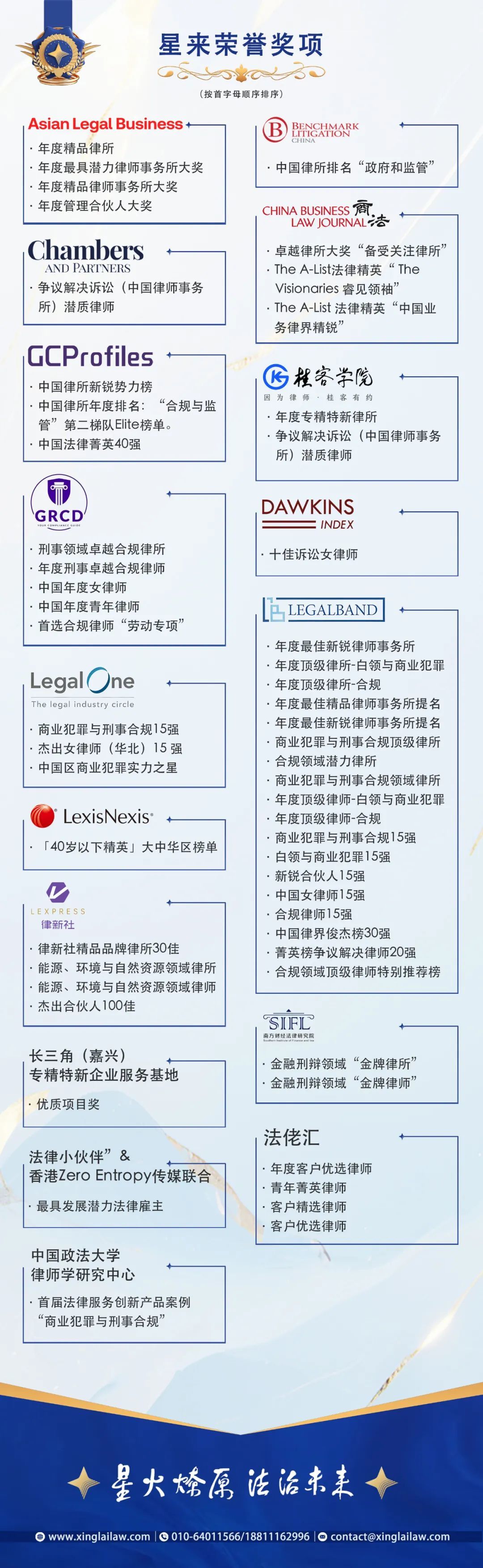

Chairperson of the Partner Meeting at Beijing Xinglai Law Firm and PhD in Law from Renmin University of China. She serves as a member of the Criminal Law Committee of the All China Lawyers Association, a specially appointed lawyer supervisor for national detention centers under the Ministry of Public Security, Vice Director of the Criminal Procedure Committee of the Beijing Lawyers Association, and Vice Director of the Judicial Credibility Committee at the Beijing Credit Association. Additionally, she acts as an off-campus mentor in criminal defense practice at Peking University, Renmin University of China, and other prestigious institutions. Notably, she was recognized in Chambers’ “Guide to the Legal Profession: Greater China 2025” in the Dispute Resolution category and named among the Top 15 Outstanding Female Lawyers (North China) and Top 15 in Commercial Crime & Criminal Compliance by LegalOne China’s Client Trusted Lawyers 2024. She was also featured on LEGALBAND China’s Special Recommendation List for Commercial Crime & Criminal Compliance in 2022. Previously, Attorney Cheng Xiaolu spent many years working within Beijing’s procuratorial system, earning accolades such as Beijing’s Outstanding Prosecutor and one of the Top Ten Research Experts. Her research achievements were honored with the First Prize in the National Procuratorial Theory Application Article Competition. With over 19 years of extensive experience in criminal justice practice, Attorney Cheng has handled numerous high-profile and impactful cases involving economic crimes, organized crime, corruption offenses, and complex criminal-civil crossover matters. She has provided specialized criminal legal services to several state-owned enterprises, listed companies, and private businesses, earning widespread praise from clients for her exceptional professional expertise and dedication.

Beijing Headquarters Address: Floor 17, East Section, China Resources Building, No. 8 Jianguomen North Avenue, Dongcheng District, Beijing

Wuhan Branch Office Address: Room 1001, 10th Floor, Huangpu International Center, Jiang'an District, Wuhan City, Hubei Province

Edited and Layouted by: Wang Xin

Review: Management Committee

Related News